|

First stop is Leigh on Sea, which hosts the closest fishing activity to London and is the capital of the estuary's cockle-harvesting business. Up until the 1980s cockles were raked from the sands by hand but today vacuum dredgers suck up them in huge quantities. There are only 14 licences to fish for cockles allocated for the whole of the Thames Estuary and eight of them are held in Leigh. While the boats supply the traditional and tourist markets in the area, most of the catch is exported to Europe. Leigh's economy grew on the raking of cockles because of the miles of sand revealed by the receding tides, which is also why Southend has the longest pier in the world - it needed to be that long so that boats could use it and people could get a glimpse of the sea at low tide. I was too early to be able to get onto the pier and was sorry to have missed White Arkitektur's Cultural Centre and Cafe which was erected in 2012. The structure was prefabricated at Tilbury Docks, shipped along the Thames and craned into position - a much more appropriate addition than the detritus I had found at Hastings. I cycled through Jaywick Sands before hitting the seafront at Clacton. I had first heard about Jaywick when it was featured in an issue of Archigram many years ago. As I recall the magazine celebrated the informal architecture of the place and the interventions made to the bungalows and shacks by their occupants. The nearest thing in England to favelas and barriadas. The Archigram Group had probably been pointed in the direction of Jaywick by the Bartlett history Professor and writer Reyner Banham who lectured on the Essex settlement to his architecture students. More recently the poorly-serviced plotland development that once provided a place of escape for east Londoners has been named the most deprived town in the UK and in 2015 was featured in the Channel 5 programme 'Benefits by the Sea.' Today, there seems to be little evidence of the delights of customisation. In comparison to Southend's 2kms long pier, Clacton-on-Sea's is a minnow at 360m. In her excellent book, Excellent Essex, Gillian Darley describes the role of entrepreneurial engineer Peter Bruff in the founding of the town. The pier opened in 1873 and visitors would arrive by sea. In the 1860s Bruff had developed Walton-on-the-Naze as a seaside resort and built a railway line connecting it to Ipswich. Before I got to Clacton I had stopped briefly in Rayleigh to take a phone call; as I moved off I dropped a small bag with my video memory cards, AirPod and GoPro chargers inside. I was ten miles down the road to Colchester before I realised what had happened and hotfooted it back to the spot where I stopped, but no bag to be seen! I set off again and was another ten miles down the road when I received a phone call. "I'm Holly Street, my father has found a bag with your name in it." I didn't have time to make another trip into Rayleigh so I arranged for the bag to be sent to my home. Thanks, Holly! and Holly's dad. From Clacton to Frinton-on-Sea was a lovely ride along their nice wide promenade with a following wind. I had to make a slight detour for the no cycling request as the route narrowed as it came to a row of beach huts perched out over the sea. Overlooking the sea at Frinton is the Frinton Park Estate which was planned in the 1930s to include 1,100 houses, a town hall, college, churches, a shopping complex, and hotel. Oliver Hill was the principal architect and selected a stellar group of young, progressive architects, including Wells Coates, Maxwell Fry, Tecton, FRS Yorke and Frederick Gibberd to design sections of the estate. But the project foundered. The modernist, experimental design and such as concrete construction proved difficult to sell. Only about 35 houses were built; Oliver Hill had designed 12 of them , of which ten survive. The style is more popular now and a number of the houses have been restored.

1 Comment

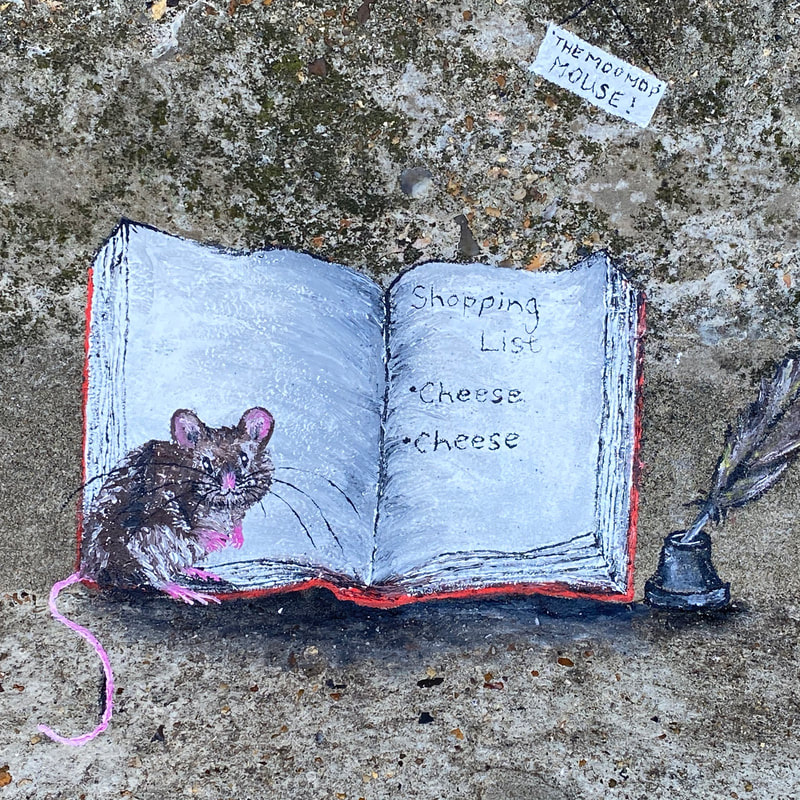

It wasn't such a great ride today though the Thames Estuary - or what I used to call the Thames Gateway. The low lying land means you're not that close to the water and the drivers in Kent and Essex are a hell of a lot more aggressive than those on the south coast. The Strava route took me on a mix of busy roads and quieter lanes. The landscape in these parts is generally gritty and flat; big logistics sheds, power lines and industrial structures dominate the low horizon. I cycled across the Isle of Sheppey to Sheerness with its busy port handling motor cars and fruit and veg. It's on the edge of England, and it feels it. Although it is a busy seaside resort I could find few redeeming features except for a delightful piece of miniature pavement art tucked away on the most deserted section of the promenade showing a mouse and its shopping list. Then on to Gillingham, Chatham - where the dockyard was sadly closed dues to COVID19 - Rochester and Gravesend. There I took the small ferry across the River Thames to Tilbury. On the north bank of the Thames sits Tilbury Fort which has protected London’s seaward approach from the 16th century through to the Second World War. Henry VIII built the first fort here, and Queen Elizabeth I famously rallied her army nearby to face the threat of the Armada. The present structure is much the best example of a star layout in England, with its circuit of moats and bastioned outworks. From there I took a detour through the Thameside Nature Park with its gravel paths until I emerged onto the dual carriageway that leads down to DP World London Gateway Port deep sea container terminal; huge lorries stacked with containers roared up and down. Strava sent me down a road that was fenced off at its end so I retraced my steps and was forced to navigate one of the most complex series of roundabouts I have ever come across chased by the aforesaid lorries and Essex boy racers. I was relieved to get to Canvey Island and pleased to be there in time to check out The Labworth Cafe which was Ove Arup's first building constructed 1932-33 which he designed to resemble the bridge of the Queen Mary. Although it looked a bit bleak with its shingle protection shutters on the front windows, you could see what Ove was getting at. Faversham to Canvey Island 133km

Dover Castle Dover Castle There’s a longish climb to get out of Folkestone, a short ride before you’re whizzing back down to sea level at Dover, through the port and up to the top of the famous White Cliffs, from which the views back to Dover Castle are spectacular. First stop of the day was Deal where I dropped in on Valerie Owen, the Master of the Worshipful Company of Chartered Architects and a local practitioner who gave me a potted history of the town: Henry Vlll’s three castles at Deal, Walmer and Sandown built to keep out the French, the smugglers and the wreckers who plundered shipwrecks on the Goodwin Sands, and the strong community ties that exist in the historic town. I then enjoyed a ride around the older parts of Deal, the Marine Barracks and the pier but was somewhat miffed at all the No Cycling signs, particularly on the pier where you aren’t even allowed to take your bike onto the pier let alone ride it. When I got to Sandwich the toll bridge across the River Stour was closed for maintenance. The bridge should have taken me on what looked like a pleasant ride across the Sandwich Estate, instead, I was forced to use the busy dual carriageway A256 to get to Ramsgate, passing Discovery Park, the former HQ of pharmaceutical company Pfizer who moved away in 2011 devastating the economy of the area. Discovery Park is now multi-occupied and rebranded as ‘Kent’s leading science park’. There is nice sweep down into Ramsgate and the Royal Harbour which forms the focus of the pretty town - spoilt somewhat by a hideous Travelodge Hotel. Apparently, Ramsgate is the only Royal Harbour in the country: it got its name from George lV who enjoyed his time there in 1821. The adjacent Ramsgate Port handles freight and passenger services, acts as a support centre for the London Array, Thanet Offshore and Kentish Flats wind farms as well as accommodating the Ramsgate fishing fleet. Most boats work within the 6 or 12-mile limits catching sole, skate, plaice and cod as well as shellfish. Local Conservative MP Craig MacKinley is bullish about the future of local fisheries post-Brexit: “I anticipate a significant dividend for our local under 10m fleet,” he says. Then on through Broadstairs to Margate on a really lovely ride, much of it along sea defences with cliffs to the left of me and lapping waves to the right. The entrance to Margate itself is disappointing - as you turn the corner into The Parade you are greeted by the backside of Chipperfield’s Turner Gallery, not one of my favourite buildings even from the front, it’s not a great welcome to the town. I do wonder just how much culture can really impact on local economies like Margate’s. I came across a rather good blog by Paul Swinney of the Centre for Cities who questions whether the brand recognition created by cultural projects brings with it an equivalent economic impact. The £68 million reportedly generated by the Turner Gallery would only equate to a maximum 0.5% of the total money created in the Thanet economy over that time, “a positive, but small number.”

What such interventions do, says Swinney, is to make such towns attractive places to live and with high-speed connections London they open up the possibility of Margate acting as a suburb of the capital. “The data offers some evidence of this happening – around 8,500 more people moved to Thanet (the local authority that Margate sits in) than moved to London between 2009 and 2017. This clearly is not a solution for a more isolated place like Scarborough or Grimsby.” I carried on along to Reculver and the striking towers of the ruined medieval church which dominate views of Herne Bay and act as a navigation marker for ships - as they had for me for the last ten miles or so. Then to Whitstable, the poster child of regenerated seaside communities. Today it is celebrated for its oysters but the industry had practically died out in the 1950s. Today good train links to London make it a draw for day-trippers, ostreaphiles and foodies generally. Then on to Faversham for the night. Folkestone to Faversham 118km 832m There were still quite strong headwinds as I left Eastbourne, passing a couple of designer beach huts commissioned by Eastbourne Borough Council as part of a programme to boost visitor numbers. The designs were nice enough but nobody seemed to be maintaining them, which rather spoilt the intended effect. A highpoint of the day’s ride was cycling into Bexhill and seeing the splendid De La Warr Pavilion, designed by Erich Mendelsohn and Serge Charmayeff, commanding the seafront. The building was constructed in 1935 and extensively refurbished by John McAslan in 2006. CABE’s Shifting Sands report celebrated the success of the pavilion’s renaissance which it calls “Crystal Palace by the sea”. The report also mentioned Niall McLaughlin’s “deceptively fragile” mobile bandstand which won a RIBA Award back in 2002. It’s not as fragile as it looks and I am pleased to report that it is in excellent shape having benefitted from a recent wash and brush up. The landscaping by HTA, funded by CABE’s (don’t you miss ‘em?) Seachange programme, elegantly ties the whole lot together. Then on to Hastings where the architectural story is not so rosy. I was looking forward to seeing dRMM’s Stirling Prize-winning pier. I knew it had had financial problems and that the new operator was not that sympathetic to the architects’ concept. But I was shocked at how dRMM’s elegant structure had been disfigured by poorly arranged and badly designed attractions. I realise that the idea was to create a platform that could support a variety of uses from circuses to music events but sadly the architecture is almost totally submerged by the tat. HAT Projects’ black ceramic-clad Jerwood Gallery further along the front, which opened in 2012, has not suffered such depredations and sits comfortably with the pitch-painted net drying towers that serve the town’s fishermen whose mainly under-10m boats make up the UK’s largest beach-launched fleet and fish for cod, skate, sole and plaice. After a 160m climb out of Hastings, the roads were flat, crossing Romney Marsh, Rye Bay and Dungeness. This Special Protection Area runs from Norman’s Bay in the west to Hythe in the east bookended between high chalk cliffs. The area includes the largest and most diverse area of shingle beach in Britain. It was originally formed by rivers draining the Weald to the north whose sediment filled the area behind the shingle beaches over time. Rye is a very pretty town. I haven’t been there for ages and was surprised at the number of visitors and the long traffic queues - a situation probably exacerbated COVID19. It is also a port with facilities for a 32-boat fishing fleet. Some of the catch is sold at the quayside, though most is sold across the channel in Boulogne. In contrast, Dungeness is not very pretty, dominated as it is by pylons and power lines leading to Dungeness B nuclear power station. You weave your way through scrubland and barbed wire fences ending up at Lydd-on-Sea probably the most depressing place on my whole journey so far. A long straight road of ugly bungalows on one side looks out over a hundred metres or so of scrubby shingle that is more like an aggregate quarry than a seaside beach. Things improved hugely, however, as I got to Dymchurch and joined the broad walkway that forms part of the coastal defences which were upgraded in 2011 to protect the town. These are around 5m wide and form a very nice cycling environment with plenty of space for both pedestrians and riders. As I cycle into Folkestone along Marine Drive I am struck by a huge building site on the beach. This turns out to be the Folkestone Harbour and Seafront Development designed by Acme Architects for Sir Roger de Haan - the wealthy philanthropist who has spent many millions supporting the regeneration of his home town. The development company has already invested in works to the harbour and the old rail station, much improving this part of the front which has been in a sorry state ever since the ferry services dwindled away in the late 1990s. Improvements include an open-air cinema, a hub for independent traders as well as restoration of the Customs House, lighthouse and viaduct. In recent years De Haan has been closely involved in bringing the arts and culture to the town, supporting the Creative Folkestone charity which, among other things, manages the Folkestone Triennal. Another plus for the town is the high-speed rail service which means it is possible to get to London St Pancras in a little over 50 minutes. Since it opened in 2009, this has helped to stimulate the local economy and generate new employment opportunities.

Despite all this, some parts Folkestone experience record levels of deprivation; the proportion of households earning less than £20,000 per annum is near twice the national average and the rate of unemployment and permanently sick and disabled is above the county average. These problems were brought home to me as I got closer to the harbour to find groups of street drinkers gathered at the base of the iconic Grand Burstin Hotel involved in a rather disagreeable punch up. As I wandered around the Old Town I came across a bar housed in a fine classic building, formerly a Congregational chapel, called The Samuel Peto. This was a bit of a surprise as I had already arranged to follow the Samuel Peto Trail when I got to Lowestoft. Where was the connection? A quick Google sorted me out. Sir Samuel Morton Peto MP was one of the great Victorian railway builders. In 1843 he bought Somerleyton Hall in Suffolk and carried out a number of developments in nearby Lowestoft. In the 1860s he got involved with the London, Chatham and Dover Railway (LCDR). A keen Baptist, he contributed to the area by funding the construction of the Folkestone chapel. Unfortunately for Peto the LCDR failed and his reputation was destroyed in the ensuring financial scandal and he was forced to retire from public life. (One can still see the crest of the LCDR on the unused columns which sit in the River Thames between Blackfriars Bridge and Blackfriars Station.) Eastbourne to Folkestone 106.65km. Elevation 643m  Background I had a few rides planned before lockdown. Right now I should have been cycling across Tanzania raising money for the architects’ charity Article 25. But that got cancelled because of the pandemic. I had a plan to bike the length of New Zealand one day. Then I started riding around west London where I was holed up as a result of lockdown and found myself in streets I never knew existed, discovered hidden paths and some really nice places. So in the spirit of the times where a hundred per cent home working has made us all more aware of our local areas, I thought that rather than emitting over 12,000 kg of CO2 flying to NZ and back, I would plan a UK trip instead. I have been fascinated by the economy of seaside towns ever since my wife Jane commissioned Thomas Heatherwick to design a cafe in Littlehampton in West Sussex on a site next to a new housing development where once had stood a splendid Victorian Beach Hotel. During the 19th century, Littlehampton had been a busy port with trade-in fishing, aggregates, Baltic timber and shipbuilding. There was a regular ferry to Honfleur and the new railway line turned the town into a seaside destination. The ferry stopped in the early 20th c and trade gradually dwindled. The town’s fortunes took a steeper dive when in the 1970s and 80s visitors forsook British beaches in favour of sunnier spots on the Costa Brava and elsewhere in the Mediterranean. The demolition of the Beach Hotel in 1994 marked the end of an era. The sea was no longer the driver of the local economy - Littlehampton, and many other seaside towns like it - had to earn a living with half the catchment area of their landlocked competitors. Heatherwick’s East Beach Cafe did its bit to put the town on the map and draw visitors. So I thought it would interesting to see how other coastal towns were coping and a ride around the coast of Britain seemed a good way of finding out. In 2003 the Commission for Architecture and the Built Environment (CABE) and English Heritage wrote an excellent report entitled ‘Shifting Sands - design and the changing image of English seaside towns’ which looked at several projects that enhanced the offer of places like Bexhill, Eastbourne, Folkestone, Jaywick Sands and Morecambe. The report set out the stark facts: in 1968 holidays in seaside resorts accounted for 75 per cent of all main holidays taken by Britons; by 1999 seaside that had plummeted 44 per cent. I thought it would be interesting to check out some of the projects featured in the report which CABE Chairman Sir John Sorrell had called ‘local heroes’. The economic and social deprivation of many seaside communities has been the topic of a series of reports and inquiries. In 2003, Sheffield Hallam University found that: “Seaside towns are the least understood of Britain’s ‘problem’ areas”. A 2008 study by the Department for Communities and Local Government noted that “seaside towns as a whole have a lower than average employment rate, an above-average share of working-age adults on benefits, lower average earnings and are more affected by seasonal unemployment than the rest of England.” Data from the 2011 census reinforced these conclusions, revealing that residents of coastal communities were less likely to be employed and more likely to have a long-term health problem than residents of other areas. A 2017 report by the Social Market Foundation (SMF), which compared earnings, employment, health and education data in local authority areas, identified “pockets of significant deprivation” in seaside towns and a widening gap between coastal and non-coastal communities. The report suggested that in Great Britain, economic output (GVA) per capita was 23% lower in coastal communities, compared with non-coastal communities, in 1997. By 2015, that gap had widened to 26%. In 2018 the House of Lords' Select Committee on Regenerating Seaside Towns and Communities published its report which showed that coastal towns score highly in the Government’s Indices of Deprivation. According to the MHCLG English Indices of Deprivation 2015, the most deprived neighbourhood in England was to the east of the Jaywick area of Clacton on Sea. This was also the most deprived neighbourhood according to the Index of Multiple Deprivation 2010. Five of the ten local authorities in Great Britain with the lowest average employee pay are in coastal communities including Torbay, Gwynedd and Hastings. There are some common issues that often characterise coastal communities. Their economies, which were already predominantly reliant upon seasonal patterns of trade, have suffered from an ongoing loss of business which has reduced opportunities for entry-level jobs, particularly for young people. As a result of this trend, the majority of seaside towns have been left with a legacy of semi-redundant accommodation and housing stock, a prevalence of Houses in Multiple Occupation (HMOs) and a distortion of local housing markets. The abundance of relatively cheap accommodation has encouraged population transience, particularly amongst vulnerable adults and children, placing additional pressures on local services. The report also suggested that inadequate transport connectivity is holding back many coastal communities with Cornwall and Lincolnshire at particular disadvantage from the impact of the Beeching rail closures of the early 1960s. Interestingly, fishing wasn’t mentioned by the Select Committee even though the sector is likely to change dramatically at the end of the Brexit transition period. COVID19 has also had an impact. In Kent and Essex local authorities have set up Fish Local to help promote local fish products. Normally 80 per cent of a catch goes to foreign markets but because of the pandemic, all major international and national markets for fish and shellfish have either closed or are limited. Neither did the Select Committee mention cycle tourism - despite Sustrans' calculations that the National Cycle Network contributes. £650 million to local economies while within Europe the sector is worth 44 bn euros. Just as COVID19 has prompted me to take my holiday in Britain, others are doing the same. The staycation will be good for the seaside in the short term. But what will be the lasting effect? All these seemed fascinating issues to study and understand as I pedalled around the coast. My bike For this first leg, I was riding a Brompton Electric, kitted out with two batteries which I hoped would last the 100 or so kilometres I would be riding each day. I keep the things I’ll need during the day in the Brompton bag on the front, my waterproofs on the rear rack and my spare clothes and things I will need in the evenings in a bag fixed to the saddle post. The whole set up is pretty hefty weighing in at 31.5 kg. I bought myself a Wahoo Elemnt Bolt for the trip having always hated my Garmin for its unfriendly interface. Using routes created on Strava and guided by Wahoo navigation was a dream. I set out from the East Beach Cafe, Littlehampton, to cycle around the coast anti-clockwise, in stages. I had aimed to do two weeks and get as far as Edinburgh, doing Scotland and the west coast in 2021, however when I got to King’s Lynn the worrying spike in COVID19 cases and new Government measures suggested it would be wise to cut the leg short. Day 1 September 19 2020. Littlehampton to Eastbourne I was seen off from East Beach by my wife Jane, daughter Sophie and granddaughter Ines. Just outside Rustington, I met up with son William who planned to ride with me to Brighton. When we got to Worthing David Taylor, editor of Velocity magazine, New London Quarterly and Brighton resident, was waiting to accompany us for the next few miles. It was a great send-off. A few miles past Brighton I would be on my own. Worthing has a nice pier; the listed Art Deco structure was named the best in Britain in 2019. Stirling Prize winners Wilkinson Eyre designed the Splashpoint Leisure Centre in 2013. To the east of the town, a stylish new block of apartments is nearing completion designed by Allies and Morrison. There are fishing boats pulled up on the beach. A couple of years ago Fishing News wrote an article on Worthing’s Beach Fishermen. “Nick Jenkins currently has two boats working from the shingle beach at Lancing, just east of Worthing, where he sells his daily catch direct to the public from his hut on the beach. The fishermen all sell direct from the beach, and this is their main source of income, as well as regularly supplying some restaurants and small hotels”. Some of the fishermen used to moor their boats in Littlehampton but increased charges moved them away. It will be interesting to see what difference the new Fisheries Bill will do when it becomes law and access for EU and other foreign vessels to UK waters will be restricted. The Bill provides powers to introduce schemes of financial assistance for the fish and fish farming industries, to improve the marine and aquatic environment, and to promote recreational fishing. The legislation “aims to ensure that the work of vessels registered in the UK chiefly brings social or economic benefits to the UK. For instance, by requiring catches to be landed in UK ports, or focusing on employing UK labour.” Next up is Shoreham with its harbour which is planned by 2031 to “ be transformed into a vibrant, thriving waterfront destination comprising a series of sustainable, mixed-use developments alongside a consolidated and enhanced Shoreham Port which will continue to play a vital role in the local economy. Not much change was in evidence except for the new Shoreham swing bridge for pedestrians and cyclists designed by engineers Cass Hayward. The graffiti-covered Beach Green toilets for which Heatherwick Studio designed a replacement cafe five or six years ago remain as they were. David navigates us on a tricky route through Shoreham harbour which morphs into Portslade Harbour where we find Brighton Fish Sales. Their website describes the fishing methods of one of their under-10m boats: “Evie Mae is an under-10m multipurpose catamaran. She can adapt fishing methods to take advantage of inshore seasonal fisheries. In the early part of the year in the cold winter months she fishes for available demersal species such as Cod, Dover Sole and Plaice. During the spring, when the weather settles and temperatures increase, the annual local Cuttlefish fishery commences. The warm summer months bring further opportunity for Evie Mae in the form of the whelk fishery. In the autumn months, whelk pots are stored ashore and replaced by static nets targeting species such as Sole, Plaice, Turbot, Brill, Skate and Pollock. Weather permitting, this method of fishing continues into the final months of the year along with opportunistic fisheries such as Sea Bass presenting themselves when conditions are optimal.” I have warm childhood memories of Hove. I used to stay in Western Esplanade (now better known as the home of Adele and D J Norman) which developed in 1910 by Michael Paget Baxter. Mrs Baxter still lived in number one and was a generous host. Although Jewish, she owned the Christian Herald whose print works were on the harbourside a few hundred metres from the house which had its now private beach. Local nuns were welcome to use the beach and sunbathed fully covered complete with veils. I was allowed to visit the print works and there grew my fascination with hot metal type which was still in use when I started work at Building Design newspaper in the 1970s. I still treasure a metal slug with my name in reverse which was made for me by one of the Herald’s typesetters - probably in contravention of the very strict rules of the National Graphical Association union. We cycled into Brighton on nice seafront cycleways. David told us of the row about Madeira Drive which was closed to motor vehicles in April which upset Conservative Councillors and caused a certain amount of traffic disruption. Calls to reopen it were turned down by Labour and the Greens. The situation will be revisited at the end of September. Forty years ago Brighton was a pretty run-down place, but today it's buzzy. The recent construction of the i360 by Marks Barfield sets the seal on its regeneration. It has a diverse local economy based around tourism, healthcare, higher education, ICT, the arts and the service sector. Tourism and hospitality-focused on weekend breaks and conferencing attract some 10 million visitors a year and employ 20% of the workforce directly and indirectly. A key benefit is that it is an average journey time of 1hour 20 minutes from London. We stopped off at the Cloud Coffee pop-up for a latte in front of the magnificent cast-iron arches of Madeira Drive. The Grade II arcade, designed by Philip Causton Lockwood (1821-1908), with cast-iron columns supporting an ironwork screen, is in a pretty dodgy state and fenced off. There is a campaign to refurbish them. David then guides me to the Undercliff walking and cycling route which as its name suggests sits under the dramatic white chalk cliffs of the east side of the city. We pass Brighton Marina with fake Georgian terraces which look as though they have been transposed to Miami with Sunseeker yachts parked outside their front door. David has to get back and I continue on to Beachy Head into a 30mph headwind which runs down the Brommy’s batteries somewhat. But it’s a short day and I have enough juice to get me into Eastbourne. You drop 150m down into the town, past grand hotels and villas that announce the town’s 19th-century heritage as an investment by the Duke of Devonshire designed by his architect Henry Currey. The current Duke apparently retains rights to the seafront buildings and protects them from development, so there is little commercial degradation. The 19th c pier suffered a major fire in 2014 but was back in use in a couple of months. The damaged parts of the structure have been replaced by simple shelters but there’s enough left to give a sense of its Victorian grandeur. The town is doing petty well. A study by Lichfields in 2017 highlighted it’s key economic features: strategic road access from the A22 and A27, reasonable rail links to Brighton and London; with particularly strong levels of growth in employment in health, residential care and hospitality sectors, as well as in professional services. Those sectors which have seen job losses include public administration, agriculture, forestry and fishing, and manufacturing. The town centre was one of the areas studied by CABE in its Shifting Sands report. I cycled around the Seaside Street area which had been the subject of a regeneration project launched in 2000. English Heritage set up a shop front restoration programme and the Heritage Economic Regeneration Scheme (HERS) put in some money. The 2003 report suggested things were getting better and announced that the “Council is now developing a major street improvement and traffic management scheme including one-way traffic flow, pavement widening, improved lighting and street furniture”. Nearly two decades later these improvements have recently been completed. I tweeted a photo and received a sharp response from local resident Robert Price “This is such a missed opportunity. The pavements are full of street clutter which makes walking difficult. The road doesn’t allow cycling, despite being in the original plan. A lot of locals are very disappointed.” I had ridden into the area through an older pedestrianised street that permitted cycling and carried on riding on the newly paved area. I missed the ‘no cycling’ signs and no one told me not to. I thought the new works were an improvement from trafficked streets even if a little flawed. Local cyclists need to campaign to get the restrictions lifted. Littlehampton to Eastbourne: 75.9km. 586m elevation

Medellin is a fascinating city. It sits in a valley with a river running, north south, down the middle. Large areas of the surrounding mountains are covered with precarious slum housing similar to the favelas of Brazil or barriadas of Peru. The traffic is terrible and there are plans to restrict cars by permitting access to odd number plates one day and even the next. It has an excellent metro system that largely runs parallel to the river and stations are linked to the four lines of spectacular Metrocable cars that span the city. The cable cars allow a transport system to be threaded into the dense slum areas with minimal disruption and efficiently traverse the steep inclines. Bus stops and cycle share are located at metro stations, providing a satisfyingly integrated system. Every Sunday and public holidays there is a cyclovia around Avenida Poblado between 7am and 1pm. I was told there are some 100km of cycleways in the city (a link to them can be found here) and so I decided to investigate. I started at the Botanical Gardens and followed a route going south. Crossings are linked to pedestrian movement rather than vehicular and marked in red - so you cross when the peds do.  The cycleway turned onto a wide street with a well marked route next to a tree-lined pavement. But then came a bit of a surprise and cyclists turning right were directed onto a lightly segregated cycleway which ran down the middle of the road which did little to prevent encroachment by vehicles or was great for peds. Then, as so often happens, it ran out of steam and cyclists were forced onto a rather narrow and at times crowded pavement. But then as quickly as it had disappeared, it started again as a shared foot/bike path: Further on I was impressed by the new connection into the University, which was very busy and included a bikeshare station. The route then went into the middle of the road again. The raised section between four lanes of traffic is safe enough for cyclists, but again, poses problems for peds. It's also pretty polluted. Then came a more successful bit of light segregation followed by a nice, wide street where cyclists are segregated from traffic by trees and from peds by bollards and planting. I then got to a Metro station where Bikeshare links up to the rest of the public transport network. The cycle route continued on through a lovely park, following the route of the Metro.  I finish with a shot of a junction protected by rather interesting bollards. I presume the holes are in there to take a chain or a rope; they provide a high degree of protection to cyclists, are easy for peds and look OK to boot. I was only in Medellin for three days and am in no way an expert, but I was very impressed by the ambition of the city to face up to some pretty amazing challenges, not least repairing the city after decades of drug trade induced violence. The charismatic Mayor of Medellin in the early noughties, who then became Governor of Antioquia state is Sergio Fajardo, a mathematician rather than a politican whose father was an architect. He saw the benefits of providing the poor with a strong social infrastructure and built an amazing array social and sports centres, libraries and hospitals in the most needy areas. There is even a spanish disctionary definition of 'fajardismo'. One cannot leave the home of Quintana, Chaves and Uran without commenting on more adventurous cycling. In spite of the competitive reputation of Colombian cyclists I saw none of the aggressive cycling one sees so often in London - although where there were no cycleways, riders were fearless as they mixed it with the busy traffic. Most impressive were the massive climbs in the surrounding mountains - on every car journey out of the centre one encounters dozens of cyclists, amateur and professional, training in the thin air.  ‘Build what British people want,’ Housing Minister Kit Malthouse exhorted architects at a recent conference to discuss his department’s Building Better, Building Beautiful Commission chaired by the right-wing philosopher Sir Roger Scruton. Malthouse believes that if the views of the British people are taken more into account by designers then new development will meet less resistance from local communities. By selecting Scruton, a devotee of classical and vernacular architecture, Malthouse assumes that the British public is only interested in the styles of the past. What better barometer of middle England taste could Malthouse have than the presenters of the BBC’s Breakfast programme? When Foster and Partners recently launched their decidedly space-age designs for an observation tower in the City of London, branded The Tulip, anchor Dan Walker called the proposed structure“a good looking building”. His co-presenter Naga Munchetty agreed but went further. She commended the tower because it was “very space-like” and then used the ‘B’ word on live television. She called the Foster design “Beautiful!” Ironically the comments from professional readers of the Architects’ Journal were less flattering likening the shape to a cotton bud, mushroom, spermatozoa and phallus. Not that that should deter the designers. When designs for 30 St Mary Axe were first unveiled one commentator dubbed the curvy structure the “erotic gherkin” in a similarly cynical vein. Since that time however the abbreviated “The Gherkin” has become the affectionate nickname for Londoners’ most favourite modern building. While such name-calling is good knock-about fun, the proposal is worthy of more serious consideration. Does London, let alone central London, even need a tower like The Tulip? After all, there are already observation platforms in The Shard and the Walkie Talkie and new ones proposed in One Undershaft and 6-8 Bishopsgate. Foster partner Grant Brooker thinks there is a substantial demand for The Tulip’s vertigo-inducing glass floors and pods. “The idea came about as a result of Open House. The queues for The Gherkin were so large they prompted Jacob Safra, the owner of the building, to ask if we could open up the space at the top to the public.” That wasn’t possible but Fosters suggested instead that the available land on the northeast of the 30 St Mary Axe site could be used to build a slim tower to house viewing platforms, bar and restaurants. The million or so visitors it was expected to attract would make it an economic proposition. “Plenty of cities have these marker buildings,” says Brooker. Fosters designed the Barcelona Communications Tower - the 288m high Torre de Collserola - in 1992; in cities like Toronto, Berlin, Tokyo and Shanghai they are popular tourist destinations providing spectacular views of the surrounding city. Our own BT Tower does just that but is sadly open for only limited periods. New London Architecture (NLA) hosts an annual reception in the revolving deck which is so popular that tickets have to be distributed by ballot. Providing new tourist infrastructure fits well with City Hall policies: in 2025, visits to the capital are expected to reach 40.4 million as long as we remain competitive and invest in culture and amenities. Those who question whether money should be spent on attractions like the Tulip when London is facing a housing crisis should realise that tourism accounts for one in seven jobs and such overseas investment benefits the wider economy. Policy E10 of the new London Plan says “associated employment should be strengthened by enhancing and extending (the capital’s) attractions, inclusive access, legibility, visitor experience and management….”. The Tulip responds to the Corporation of London’s own strategy to bring more people into the Square Mile to create a seven-day-week “retail, leisure and cultural destination”.The draft City Plan says “complementary land uses will be encouraged to enhance vibrancy and viability, extending to weekends to diversify the City, its economy and community”. At the moment tourists flock across the Millennium Bridge to St Paul’s Cathedral and don’t get much further east than the One New Change shopping centre. More has to be done if the crowds are to move into the heart of the City: try and find an open coffee shop on a Saturday morning! The attraction of the Walkie Talkie’s difficult-to-access viewing gallery has increased the number of visitors somewhat in EC3 but not enough to get the shops to open. The City Plan also speaks of improving the offer at Leadenhall Market, a couple of minute’s walk from the site of The Tulip: “the character of the historic market will be maintained and enhanced as a visitor and retail destination, supporting a flexible range of retail uses.” The Tulip’s planned exhibits and educational programme will add to visitors’ understanding of the City. As someone who spends much of his time attempting to communicate issues around development and change in London to a wider public audience, this will be a spectacular new tool. It will also enhance the Corporation’s cultural strategy which at the moment is focused on the north-west part of the City around the Barbican Centre, the Museum of London and the proposed Centre for Music. More attention needs to be paid to the south - to the amazing heritage of the City churches, of the historic Livery Halls, the Guildhall and the riverside walk which, in spite of being on the sunny side of the river, has a fraction of the numbers of visitors that use the South Bank. There is some understandable concern that the popularity of The Tulip will mean that the already overcrowded City pavements will become even more so, although Brooker suggests that because of the different schedules of workers and tourists this won’t be a major problem. Anyway, if the City implements its excellent proposed Transport Strategy which promotes improved pedestrian movement, overcrowded pavements will be less of an issue. Norman Foster himself describes the Tulip proposal as being “in the spirit of London as a progressive, forward-thinking city.” It is in the smooth, steel and glass, engineered style we see in The Gherkin and in the work the practice does for clients like Apple, which has its roots in the high tech movement of the 60s and 70s. Coincidentally, the building was launched in the same week that the eponymous radical architecture group published Archigram: the book. A key Archigram project was the Montreal Tower by Peter Cook - designed some 55 years ago -which might be seen as a precursor of The Tulip with entertainment spaces, views and restaurants on top of a slim stalk. The aesthetic is slicker and more sophisticated but the spirit lives on. At 305.3m The Tulip will be marginally higher than the proposed One Undershaft next door and shorter than the Shard’s 309.7m across the river; its bulbous, mini-gherkin pinnacle will sit comfortably above the walkie-talkies, cheesegraters, scalpels and cans of ham below. The gallimaufry of designs that make up the easter cluster can easily absorb a new friend. As the scale of the latest orthogonal towers - 22 Bishopsgate and 100 Bishopsgate - becomes apparent, it is clear that the townscape can only take a few such behemoths. There is still a role for the sort of varied geometry that has defined the City over the past decade and has proved popular with the public. Indeed, when NLA carried out research into the number of towers being built in London a commonly heard complaint was that their views of The Gherkin were being blocked by the new developments. Among younger audiences, this was seen as just as damaging as any impact on views of St Paul’s Cathedral dome. In the build-up to the Olympics The Gherkin became a key part of brand London: gone were the beefeaters and Buckingham Place, in came images of modernity and progress. Fosters’ latest design reflects that vision of a contemporary City, a city of culture and creativity. Is it beautiful? That is, of course, a matter of taste, but when it comes down to defining an acceptable contemporary aesthetic, I’d go with Munchetty over Scruton every time. Image: DBOX for Foster + Partners Correction: This article was amended on 26 Nov 2018 to clarify that it was not Rowan Moore who christened 30 St Mary Axe as the 'erotic gherkin'. On Saturday 24 April 1993 at 9.17am, the City of London Police received a coded warning from the South Armagh Brigade of the IRA. Just over an hour later a bomb in a tipper truck parked in Bishopsgate and loaded with almost a ton of fertiliser was detonated, destroying adjacent buildings and severely damaging many others within a 500m radius. The cost of building repairs was estimated at £1billion.

The IRA bombing campaign set in train a series of events that led to an equally dramatic but more benign change in the architecture of the Square Mile - the rise of the Eastern Cluster. The close-kissing towers, still growing on the City skyline - once dominated by Wren’s 51 church spires - have multiplied ever since Foster and Partners received planning permission for 30 St Mary Axe in 2000 on a site made vacant by the 1992 Baltic Exchange bomb. One of the victims of the IRA was the Leatherseller’s Livery Company Hall in St Helen’s Place, set behind a neoclassical facade built in the early 1900s. As the ancient Company, which dates back to 1444, contemplated restoration, it became clear that surrounding sites of which it held the freehold were ripe for development. The Square Mile was booming and the City Corporation was keen to densify office space. As then Planning Chief Peter Rees said, “if we can’t build out we must build up.” The outcome was that the Leathersellers did a very advantageous deal with Brookfield Properties whereby the developer would build the 40 storey 100 Bishopsgate Tower next to the site of the old hall and the proceeds would fund a new one - no expense spared. Instead of building up, Eric Parry designed a building that goes down. Behind the refurbished facades of Helen’s Place, the above-ground floors have been allocated to income-generating office space while a grand ground floor reception space, with views out to the medieval walls of St Helen’s Bishopsgate, leads to a sweeping, processional stair down to the Company’s dining hall. The curved walls are lined with shrunken bull shoulder with a two-tone effect developed by leather designer Bill Amberg, to match the vitreous enamel on the building’s exterior. Elsewhere, Amberg has responded to Parry’s obsession with craft to fill the Hall with a range of leather pieces including a corridor lined with pale green and maroon, gold-foiled, leather-clad panels and an inglenook in the ground floor lobby area entirely stitched by hand using historic saddlery techniques. Craft, not just in leather, is a key focus of Parry’s interior: the Court Room has double height panels of American walnut with a central court table of European walnut; the reception room sports a central blue-and-white glass sculpture by Dale Chihuly suspended above a circular bronze table, while the carpet was designed by Parry to complement the Chihuly above. At the top of the main staircase is a stained-glass window by Leonard Walker showing Henry VI, the monarch who conferred the first Charter on the Company made in 1937 for a previous hall. Scagliola pilasters, transferred from the old Hall, have been scattered randomly across the walls and ceilings - perhaps as a reminder of the destruction of previous halls by the Great Fire, the Blitz and the IRA bombings. The walls of the Dining Hall are again covered in American walnut panels which sit below a forty metre long tapestry with images and allusions relating to the Leathersellers’ Company and its history. The Hall was opened in 2017 by the Earl of Wessex and is a worthy new member of the cluster of City Livery halls that is such an important and little-known component of London’s heritage. The importance of this collection of architectural gems can be discovered in a remarkable new book by Dr Anya Lucas and Henry Russell with photos by Andreas von Einsiedel. I use the word remarkable advisedly. Astonishingly, this is the first time in their long history that the 40 historic buildings have been properly photographed and compared. Thanks to the initiative of the Worshipful Company of Chartered Architects it is now possible to properly appreciate the legacies of the ancient City trades like the Mercers, the Grocers, the Goldsmiths and the Skinners. It is to be hoped that the publication will prompt the generally secretive Companies to make their homes more accessible to the wider public and in that way to highlight the rich culture of the Square Mile. The Livery Halls of the City of London Anya Lucas and Henry Russell Photography by Andreas von Einsiedel is published by Merrell on behalf of the Worshipful Company of Chartered Architects. 280 pp and 450 illustrations. https://bit.ly/2P0Me2k Price £45 |

Archives

October 2020

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed