Cyclists in Bank Junction protest at the death of Ying Tao, killed by a construction vehicle Cyclists in Bank Junction protest at the death of Ying Tao, killed by a construction vehicle When London planning consultant Francis Golding was killed by a left-turning coach while cycling home in November 2013, a group of friends and business associates got together to see what they could do to improve cycling conditions in the capital. In that dreadful month six cyclists were killed on London’s streets and it became clear, as the group studied the statistics, that construction industry vehicles were responsible for a disproportionate number of fatalities. So the group decided to focus on their own area of business - development and construction - to see specifically what could be done to help the industry improve its dire record. So the Construction Industry Cycling Commission was set up; chairman of the group was Mike Hussey, CEO of Developers Almacantar. Mike had been involved with Francis on the planning of the Walkie Talkie tower in the City of London. Other members included Michael McGee of the McGee Group, who are contractors with a large fleet on lorries, as well as architects, planners and contractors. Momentum for the Commission built up with the deaths of Claire Hitier-Abadie and Moira Gemmill in 2015, both involved with the industry and both killed by construction vehicles. Early discussions of this rather disparate group made it clear that it needed to have some sound information on which it could base any future work. So it commissioned research from Phil Jones Associates and TMS, a company specialising in road safety and traffic management, to try and find out why the building industry was doing so badly and what could be done to improve the situation. The research figures revealed that whilst HGVs account for only 3.5% of traffic across London, they are involved in 57% of crashes in which a cyclist has been killed (2007 – 2014). It found that 76% of collisions occurred at junctions, 62% of cycle fatalities at traffic signals involve large vehicles turning left or moving off, with most cyclists being struck by the front or nearside of the vehicle. Many fatalities involve HGVs in the construction industry. The research team organised workshops with industry representative to ascertain how best to respond to the findings. As a result a ten point manifesto was agreed: 1 For all property developers and contractors to recognise that health and safety on the road is as important as it is on site 2 For cycle safety to be recognised as part of the Considerate Constructors’ accreditation, ensuring that all lorries used on sites have the requisite safety features, and that drivers are properly trained 3 For the industry – large and small organisations – to adopt the CLOCS standard as a default requirement on all construction schemes in London and other major cities, and wherever significant interaction between HGVs and cyclists can be expected 4 For investment in safer vehicles to be made ahead of regulation, such as direct vision cabs, skirts, and specific safety standards and equipment 5 For the construction industry to fast-track discussion and action around changes to vehicle safety, which might include the retrofitting of older vehicles and retiming of journeys to avoid morning peak hours 6 For design professionals to be better trained in the design and planning of safer environments for vulnerable road users 7 For property developers to use hoarding and wraps of new developments to deploy helpful safety advice for cyclists and drivers 8 For the construction industry to support training for all road users 9 For the construction industry to support the campaign for greater separation between cyclists and HGVs in time and/or space at junctions and on links, and helping to disseminate information on primary routes used by HGVs 10 For the construction industry to support more detailed research to understand the circumstances surrounding lorry/cyclist collisions to identify the root cause of injuries, fatalities and near misses “The level of cycling accidents in the UK is simply unacceptable.” says Mike Hussey. “The CICC’s manifesto for change sets out clear ways we can improve cycle safety. As an industry, we have an obligation to improve the dangerous conditions cyclists face, so I urge our peers to join us and commit to our recommendations.” The Commission will now be pressing professional institutions, companies and consultancies to sign up to the manifesto.

1 Comment

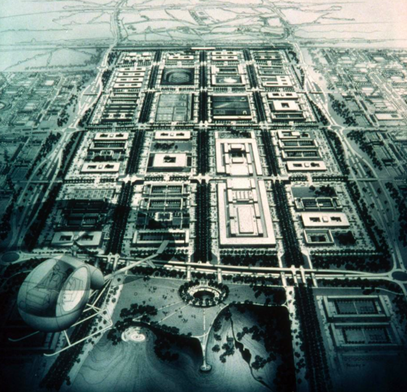

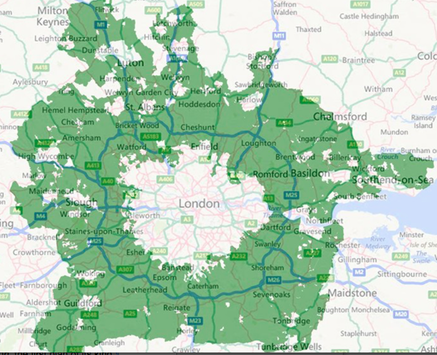

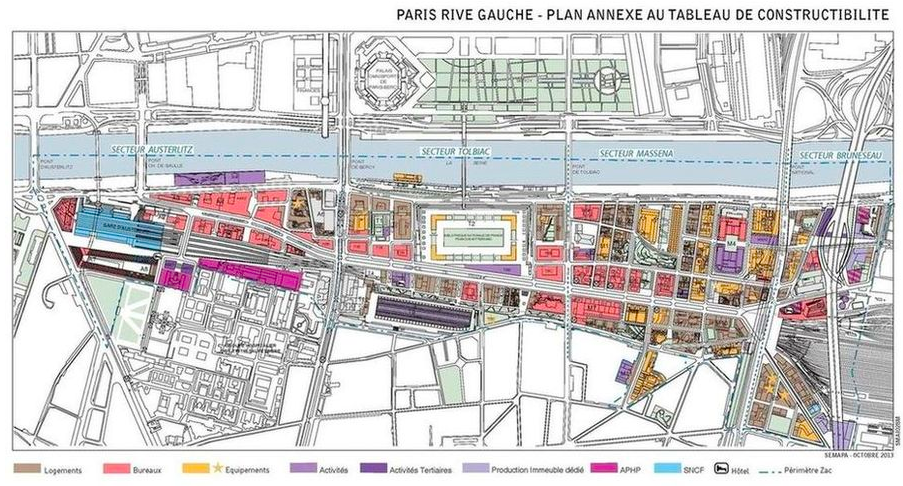

Mayoral candidates Zac Goldsmith and Sadik Khan Mayoral candidates Zac Goldsmith and Sadik Khan What sort of city do we want to live in? It’s a question that is likely to be asked many times over the next few months as London’s Mayoral candidates joust in the run up to the election in May. Do we want more tall buildings? Can we intensify the suburbs? What should we do about the Green Belt? How do we plan for development in the wider South East region? As the capital’s growth continues exponentially we need to question whether we have the right planning methods in place to create a liveable and sustainable city. London’s planning is based on negotiation and pragmaticism rather than on a grand vision like many European cities. We respond to commercial and social pressures and adapt accordingly. That has been the case ever since the merchants of the City of London rejected Wren’s renaissance plan after the Great Fire and instead rebuilt their premises on their existing sites, thus retaining the old medieval layout. This pragmatic approach is key to creating the varied character of London’s streets and places, the “city of villages” or what Peter Rees calls “the greatest unplanned city in the world.” But have the pressures of growth and global finance become too powerful for our empirical methodology? Do we have the right tools to deal with the divisions created by development whether in the the council estates of the 50s and 60s in Tottenham, Elephant and Castle and Earls Court or in the leafy suburbs of west London? What can we learnt from other cities? I remember as a student making a special trip to Sweden to study the new town of Vällingby outside Stockholm where the architect Sven Markelius had taken this English typology to a new level with high density housing around the metro links surrounded by lower rise suburban homes. Today visitors to Sweden still have something to learn from their approach to delivering new urban environments. Many architects, planners, politicians have made the pilgrimage to projects like Hammarby Sjostad in Stockholm, a brownfield site that has been developed as an exemplar sustainable neighbourhood. The city started thinking about it at the same time John Prescott launched the Millennium Village at Greenwich Peninsula with a plan to create an urban district which would be socially and environmentally sustainable with some 10,0000 homes - about the same as Hammarby. Hammarby is a medium density, walkable with good transport and cycling links to the rest of the city and makes a fascinating contrast with Prescott’s dream. At Greenwich, made up largely of publicly owned land, there was a master plan for the site designed by Richard Rogers and Partners and Ralph Erskine - who was English by birth but did most of his work in Sweden - designed the first couple of phases. At Hammerby the process started with a strategic Masterplan, that divided into site into twelve sub-districts, the City then worked with a number of architects and planners to come with an agreed detailed Master Plan. They then prepared a comprehensive design code for each sub-district which sets out principles for the district character, the mix of businesses and uses, density, built form (blocks built around inner courtyard or play area), public spaces and relationship to the water. The code provided broad guidance on architectural style: that it should reflect the character of Stockholm’s inner city; building form and architectural style to reflect hierarchy of open spaces with taller, more prominent buildings along the waterfront; preserving the natural environment; access to green space, flat roofs, clean lines and light colours. There is also an emphasis on mixed use rather than separation of uses. Finally,the City invited a consortium of developers and architects to take forward the development of each plot or individual building within the sub-district. The result is a coherent, ordered and highly sustainable piece of city. In London, developers Countryside built about a 1000 of Erkine’s buildings; after which there was a long delay while Lend Lease and Quintain failed to make any progress. The Rogers’ plan (adapted by Terry Farrell in the meantime) was forgotten and in November this year Knight Dragon received permission for a master plan designed by Allies and Morrison that brings the total potential homes on Greenwich Peninsula up to 20,000 more than double the original plan. Different folks. different strokes. Hammarby is Stockholm, it is imbued with Swedish values. It is of its time and of it place. The flexibility permitted by our planning system has certainly allowed the GLA to adapt the plan to the changing population. But will the new Peninsula feel like a part of London? Should it? Or do we remain a “city of villages” that reflects the global and diverse nature of the 21st century capital? I look forward to discussing these and other issues on London’s planning issues with Zac and Sadik in the months to come.  Farrell Grimshaw's innovative Park Road flats Farrell Grimshaw's innovative Park Road flats Why don’t we design housing more like office buildings? Commercial developers could teach the housebuilding industry a thing or two about flexibility. The traditional London terrace house has, of course, been able to adapt over the years to a whole lot of different uses, sizes of families and levels of housing supply. Just knock down a stud partition here, stick in an RSJ there, and you can transform your accommodation. Today’s housing doesn’t seem to have that inbuilt ability to change. Planners and developers specify complex arrangements of housing mix which the architect jigsaws into the site, creating fixed floor arrangements. A building that really took the idea of flexible living to heart is Farrell and Grimshaw’s Park Road flats close to Regent’s Park. The 11-storey block was one of the first co-ownership projects funded by the Housing Corporation and was designed in the late 1960s by Farrell Grimshaw for a housing association that Terry Farrell and Nick Grimshaw set up themselves. After completion they moved into the block’s penthouses. The building’s corrugated aluminium cladding, radiuses corners and continuous bands of windows certainly have the look of an office block. And just like an office building, bathrooms, lifts and stairs are concentrated in the central structural core which allows most internal walls to be non-load bearing and accommodation changed radically over time - flats can morph from one bed to a whole floor. Park Road was listed in 2001 for its ''freestanding columns, continuous perimeter heating and regularly-spaced electrical sockets encourage maximum flexibility, its curved corners give an added sensation of panoramic views by removing the need for corner mullions, the architectural effect of its minimalism is a finely proportioned, architecturally sensitive sense of space'' It was seen as an important example of British high tech. and just as high tech has rather gone out of fashion, so the sort of flexibility it delivered has been forgotten. Developers taking advantage of permitted development rights that allowed them to alter office buildings to residential without planning permission should have taken note of Farrell Grimshaw’s prototypical building and made maximum use of cores and the ability to employ non-load being partitions. They could also emulate John Habraken who in his seminal seventies book ‘Supports’ looked at the idea of self-build, shell and core apartments built within an office-style structure. Habraken’s ideas predated the Torre David - the 40-storey empty office block in Caracas designed by Enrique Gomez, taken over by squatters who ‘fitted it out’ to suit their lifestyles. The tower has been featured at the Venice Biennale, and was a rather bleak backdrop to several episodes of the Homeland TV series. It is certainly one way that self build and community housing can be delivered in urban environment. Not all homes need to be flexible of course - mansion blocks have worked pretty well for 150 years or so - but we need to get the balance right, particularly in an era when space standards are not as generous as they were in the 19th century. Office design seems to be better at creating that balance right now than housing design.  Early rendering of the Central Milton Keynes master plan Early rendering of the Central Milton Keynes master plan June 2015 was a sad month for planning. The funerals of two giants of the profession, from two very different eras, were held within a week of each other. The careers of Derek Walker, architect and planning officer of Milton Keynes in the early 70s, and Clive Dutton, who had been Director of Regeneration at Newham during the build up and delivery of the 2012 Olympics, reflected very different eras of city making. Although the firm of Llewellyn-Davies Forrestier Weeks and Bor was responsible for Milton Keynes’s Los Angeles-style layout, it was Walker who set the character and style of the place. The last of the post war new towns, Milton Keynes was also the last piece of detailed comprehensive planning to take place before the public sector was dismantled by Mrs Thatcher. Walker’s funeral ended with the singing of William Blake’s Jerusalem and it was hard not to feel a lump in the throat as we sang “Nor shall my sword sleep in my hand: till we have built Jerusalem, In England's green & pleasant land”. Landscaping was at the heart of Walker’s vision for Milton Keynes and as the funeral congregation filtered out into the city - the summer foliage in its prime - they could see for themselves the success of the mature infrastructure; a place that was both green and very pleasant. By contrast Clive worked with existing cities in a period when ‘planning’ had become interchangeable with ‘development control’. But he had great boldness vision. A man of energy, passion and boyish enthusiasm, his vision and appetite for change brought to mind Chicago planner Daniel Burnham’s quotation: “Make no little plans; they have no magic to stir men's blood.” Clive liked nothing more than standing in front of an audience, armed with a powerpoint of outrageous images, and stirring its blood with plans for improving places and people’s lives. It is apposite that when he was Director of Planning at Birmingham City Council his strategy was christened the “Big City Plan”. I helped Clive with the exhibition of Mecanoo’s winning scheme for the new Birmingham library. Today, the building’s distinctive facade of interlocking circles, dominates Century Square and is a key part of the legacy Clive gave to the city which also includes the ongoing Big City Plan and the £600 million New Street station redevelopment. When Clive took over as Head of Planning in 2005, the city boasted the largest local authority planning and development department in the UK, covering planning, regeneration, economic development, major projects, architecture, urban design, building consultancy, highways and transportation, with a development portfolio of £20 billion. Such was the ambition that, in the depths of the recession, Clive flew to China with the idea of setting up a Bank of Birmingham funded in the Far East with the second city’s enormous land holdings as collateral. In 2009 he moved to Newham, the principal host borough for the Olympics. There he was responsible for the Metropolitan Stratford Masterplan, the regeneration of the Royal Docks and Canning Town as well as the borough’s Core Strategy and Local Development Framework. Derek and Clive operated in very different climates, but they were both driven by powerful visions. As Fred Lloyd Roche, the general manager of Milton Keynes, also an architect, said in a special issue of Architectural Design on the new town that I edited way back in 1973 “If you set yourself piddling goals, you get piddling achievements.”  Paris Rive Gauche is a development to the east of the centre of the French capital. The site covers an area of 130 ha and includes suburban and long distance railway lines and sidings emerging from Austerlitz station. Some twenty years ago SEMAPA (Société d’Etude, de Maitrise d’Ouvrage et d’Aménagement Parisienne) - a sort of development corporation - drew up a master plan for the area. This included decking over 26 ha of tracks and drawing up a series of volumetric blocks that would be sold to developers who would then design buildings to fill in the blocks. Although the developers would choose their own architects - in consultation with SEMAPA - groups of blocks would be curated by a chosen architect/masterplanner. Now that sections of the plan are complete and in use one can see how the finished product mirrors the original plan and start to understand some of the lessons it might have for London. French planning lacks the flexibility if the English system. Is this a good thing or a bad thing I wondered as I visited Rive Gauche with a group of London planners recently. The grand avenue that runs through the the centre of the site, long and straight to follow the rails tracks beneath, suffers from a rigidly controlled eaves height and flat facades. It fails to deliver the sort of boulevard effect that the French normally do so well. However as you turn off into the side streets the character changes - here a tighter grain, landscaping and well designed resi buildings create a delightful series of new spaces. This is particularly the case in the area around the Diderot university overseen by Christian de Portzamparc. What interested me about Rive Gauche is that as a development it is almost exactly the same size as Old Oak Common, an Opportunity Area in the current London Plan with the aim of delivering some 19,000 new home homes. Old Oak Common is also riven with railway lines and will mark the conjunction of HS2 and Crossrail. The Mayoral Development Corporation set up by Boris Johnson is currently working on the master plan for the area and several of its key people were on the trip to Rive Gauche. So what can one learn from seeing how the French do things? First that a rigid master plan is no guarantee of quality place making, the inbuilt flexibility of the less dirigiste English system delivers greater variety and interest to the street scene. But if you want to create a coherent piece of city do you need tighter controls than is the case in current opportunity areas? Should you deck over rail lines? This is clearly important of you want to create permeable pieces of city but the technical issues are formidable - SNCF insists that the French contractors could only work for two hours each night, - and Network Rail are not known to be much more cooperative. In the end it comes down to cost - even the French find it an expensive way of creating land. The master plan for a site the other side of the Seine, also with multiple rail lines and currently being designed by Rogers Stirk Harbour, has eschewed decking in favour of islands of development connected by bridges on the grounds of cost. Perhaps the most interesting lesson of all was when the group visited the offices of APUR, the City’s Urbanism Studio, whose offices were appropriately on the 15th floor of municipal offices with a stunning view of tout Paris from their outside terrace. Such a vantage point allows you to see that although the very centre of the city is low rise, Paris is ringed by towers - over a hundred of them - and not just at La Defense. With tall buildings on the agenda at Old Oak Common and the need to densify outer London’s town centres, is this the future shape of the UK capital?  Why can’t we talk more rationally about the Green Belt? For Tory politicians terrified of knee jerk reactions from Daily Telegraph readers it is a toxic subject. Housing Minister Brandon Lewis’s instant reaction to Urbed’s winning Wolfson Essay on garden cities is an example. Urbed suggested taking bite-sized chunks out of the Green Belt but ‘the Government is committed to protecting the Green Belt from development as an important protection against urban sprawl’ spluttered the Minister, and thus the Wolfson ideas ‘will not be taken up’. However local authorities already have the power to de-designate Green Belt land in their local plan where there is a clear housing need, and boroughs around London are looking at taking lots of little bites in piecemeal fashion. The Green Belt is a key planning legacy of the last century, and deserves better. The concept was promoted in the early days by The London Society which recently published a White Paper on the subject in which planner Jonathan Manns argues that we should understand the history and remind ourselves what the Green Belt was designed for in the first place in order to think logically about its future. David Barclay Niven, one of the founder members of The London Society, writing in the Architectural Review in 1910, proposed an ‘outer park system, or continuous garden city right round London, [that] would be a healthful zone of pleasure, civic interest, and enlightenment’. In 1919 this was included in The London Society’s Development Plan of Greater London, the first plan of its kind. A quarter of a century later Patrick Abercrombie presented his own Greater London Plan to the Society where he stressed the balanced content of the Plan and the need to ‘preserve a large amount of country as near to the town as possible not only for the sake of recreation but for the purpose of obtaining fresh food rapidly’. This created an ambiguity between the domestic, recreational and agricultural purposes of the Green Belt resulted in a lasting tension which has often obscured the historically accepted recognition of land for both development and urban containment. A situation compounded by the Ministry of Housing and Local Government who said that the reasons for designating Green Belt were to check the growth of a large built-up area and to prevent neighbouring towns from merging into one another and added an extra section about preserving the special character of a town. The 2012 NPPF suggests ‘the fundamental aim of the Green Belt policy is to prevent urban sprawl by keeping land permanently open; the essential characteristics of Green Belts are their openness and their permanence.’ Then this year, Boris Johnson’s draft London Infrastructure Plan 2050 (2014) raised the issue of ‘the role that new towns and urban extensions can play in areas beyond the Green Belt’ and identified ‘major growth potential’ on land north of London, leaping over the Green Belt - which extends in places to some 35 miles from London - with the consequence of hugely increased commuter journeys. The story of the Green Belt suggests a flexible concept which has evolved and responded to the opportunities and challenges of history. Today we have a fixed entity, which our decision makers fear to discuss, with landscapes and places of beauty that deserve protection as well as plenty of golf courses and grotty bits. As Manns suggests it is time for rational analysis and a clear direction for the Green Belt of the future. Download the Green Belt White Paper here http://www.londonsociety.org.uk/blog/  Gehry's design for Facebook Gehry's design for Facebook A few years ago I went to a lecture by Frank Gehry at the Said Business School in Oxford where the great architect talked about the way he ran his practice. When he presented to potential clients, he said, he didn’t focus on his iconic style, on his sculptural forms and complex aesthetic - he told them that through his sophisticated BIM software, developed in conjunction with the French aerospace giant Dassault, not only could he could deliver his brand of architecture at 30 per cent less than traditional design methods, but he could do so on schedule. In one brilliant stroke he met head-on the usual client reservations about ‘designer’ architects and their ability to handle time and money. I am a visiting professor at the IE University in Madrid where the architecture school collaborates with the business school to run an excellent Masters course in design and management aimed at young, ambitious architects wanting to work internationally. In my lectures I use this story as an example to students of how to present themselves to clients and to show that good business practice is not just the preserve of the ‘commercial’ architect. So I was interested to read recently that Mark Zuckerberg, the founder of Facebook, “praised Gehry’s down to earth approach.” Zuckerberg had feared that Gehry would be very expensive and send the wrong signals about the Facebook culture. But it turned out that he lived up to the explanation he gave at the Oxford lecture. Zuckerberg’s comments are interesting in the light of fact that as well as Facebook building themselves a new HQ - Google and Apple are doing it too - each seeking the ideal working environment for the 21st century. Facebook wanted a building in which they could “create the same sense of community and connection among our teams that we try to enable with our services across the world.” So Frank designed a 430,000-square-foot open plan space - the largest in the world - with a 9-acre park on the roof with walking trails and spaces to sit and work. The architecture is pretty basic for Gehry with a series of orthogonal boxes crashing into each other. According to Gehry "Mark wanted a space that was unassuming, matter-of-fact and cost effective. He didn’t want it overly designed. It also had to be flexible to respond to the ever-changing nature of his business.” This is in contrast with the new Apple building designed by Foster and Partners. Foster himself has been closely involved in the donut-shaped building and had regular meetings with Steve Jobs when the Apple founder was still alive and has been dealing directly with design chief Jonny Ives since then. The building is as tightly and finely designed and engineered as any Apple product (or Norman building) but with a plan that provides for engineered change rather than the loose flexibility of Facebook’s extendable spaces. The proposals by Bjarke Ingalls and Thomas Heatherwick for Google are also loose fit in a Buckminster Fuller sort of way, with a big tent (dome) covering a diverse collection of spaces and volumes. This radical departure from the conventional box was a eureka moment for Google CEO Larry Page. Google workers have long been known for their quirky working environments so beloved of the ‘creative’ industries but Ingalls and Heatherwick went beyond quirky. So much so that Simon Allford of AHMM was called to California for a ten-minute meeting with Page to be told that Google were reevaluating the company’s design This article first appeared in On Office magazine. |

Archives

October 2020

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed