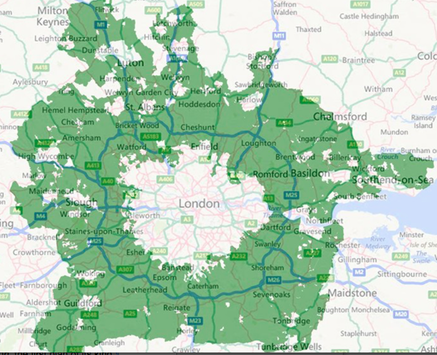

Why can’t we talk more rationally about the Green Belt? For Tory politicians terrified of knee jerk reactions from Daily Telegraph readers it is a toxic subject. Housing Minister Brandon Lewis’s instant reaction to Urbed’s winning Wolfson Essay on garden cities is an example. Urbed suggested taking bite-sized chunks out of the Green Belt but ‘the Government is committed to protecting the Green Belt from development as an important protection against urban sprawl’ spluttered the Minister, and thus the Wolfson ideas ‘will not be taken up’. However local authorities already have the power to de-designate Green Belt land in their local plan where there is a clear housing need, and boroughs around London are looking at taking lots of little bites in piecemeal fashion. The Green Belt is a key planning legacy of the last century, and deserves better. The concept was promoted in the early days by The London Society which recently published a White Paper on the subject in which planner Jonathan Manns argues that we should understand the history and remind ourselves what the Green Belt was designed for in the first place in order to think logically about its future. David Barclay Niven, one of the founder members of The London Society, writing in the Architectural Review in 1910, proposed an ‘outer park system, or continuous garden city right round London, [that] would be a healthful zone of pleasure, civic interest, and enlightenment’. In 1919 this was included in The London Society’s Development Plan of Greater London, the first plan of its kind. A quarter of a century later Patrick Abercrombie presented his own Greater London Plan to the Society where he stressed the balanced content of the Plan and the need to ‘preserve a large amount of country as near to the town as possible not only for the sake of recreation but for the purpose of obtaining fresh food rapidly’. This created an ambiguity between the domestic, recreational and agricultural purposes of the Green Belt resulted in a lasting tension which has often obscured the historically accepted recognition of land for both development and urban containment. A situation compounded by the Ministry of Housing and Local Government who said that the reasons for designating Green Belt were to check the growth of a large built-up area and to prevent neighbouring towns from merging into one another and added an extra section about preserving the special character of a town. The 2012 NPPF suggests ‘the fundamental aim of the Green Belt policy is to prevent urban sprawl by keeping land permanently open; the essential characteristics of Green Belts are their openness and their permanence.’ Then this year, Boris Johnson’s draft London Infrastructure Plan 2050 (2014) raised the issue of ‘the role that new towns and urban extensions can play in areas beyond the Green Belt’ and identified ‘major growth potential’ on land north of London, leaping over the Green Belt - which extends in places to some 35 miles from London - with the consequence of hugely increased commuter journeys. The story of the Green Belt suggests a flexible concept which has evolved and responded to the opportunities and challenges of history. Today we have a fixed entity, which our decision makers fear to discuss, with landscapes and places of beauty that deserve protection as well as plenty of golf courses and grotty bits. As Manns suggests it is time for rational analysis and a clear direction for the Green Belt of the future. Download the Green Belt White Paper here http://www.londonsociety.org.uk/blog/

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

October 2020

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed